Exhibition Room 1

Exhibition: Signed, Sealed, & Undelivered

IN 2015, THE SSU TEAM BEGAN TO RESEARCH A 17TH-CENTURY TRUNK OF LETTERS THAT RAISES EXCITING QUESTIONS.

WHY WERE THESE LETTERS NEVER DELIVERED?

WHO SENT THEM AND WHAT ARE THEY ABOUT?

DISCOVER THE SECRETS AND MATERIAL FEATURES OF THESE LETTERS...’

The Postmasters

The 17th-century trunk of letters once belonged to postmasters Simon de Brienne and Marie Germain. Who were they? And what did postmasters do?

Willem van Sundert, staircase, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

A postmasters’ home

This beautiful and exuberantly carved staircase was the way you would enter the postmasters’ house in The Hague.

Simon and Marie had it commissioned in 1698 when they bought their town house, located in the most expensive part of The Hague, the Vijverberg. As postmasters they gained astonishing wealth and power, which gave them access to the stadholder’s court. The oak and lime wood staircase was thus not simply decoration: it embodied Simon and Marie’s prominence and opulent lifestyle.

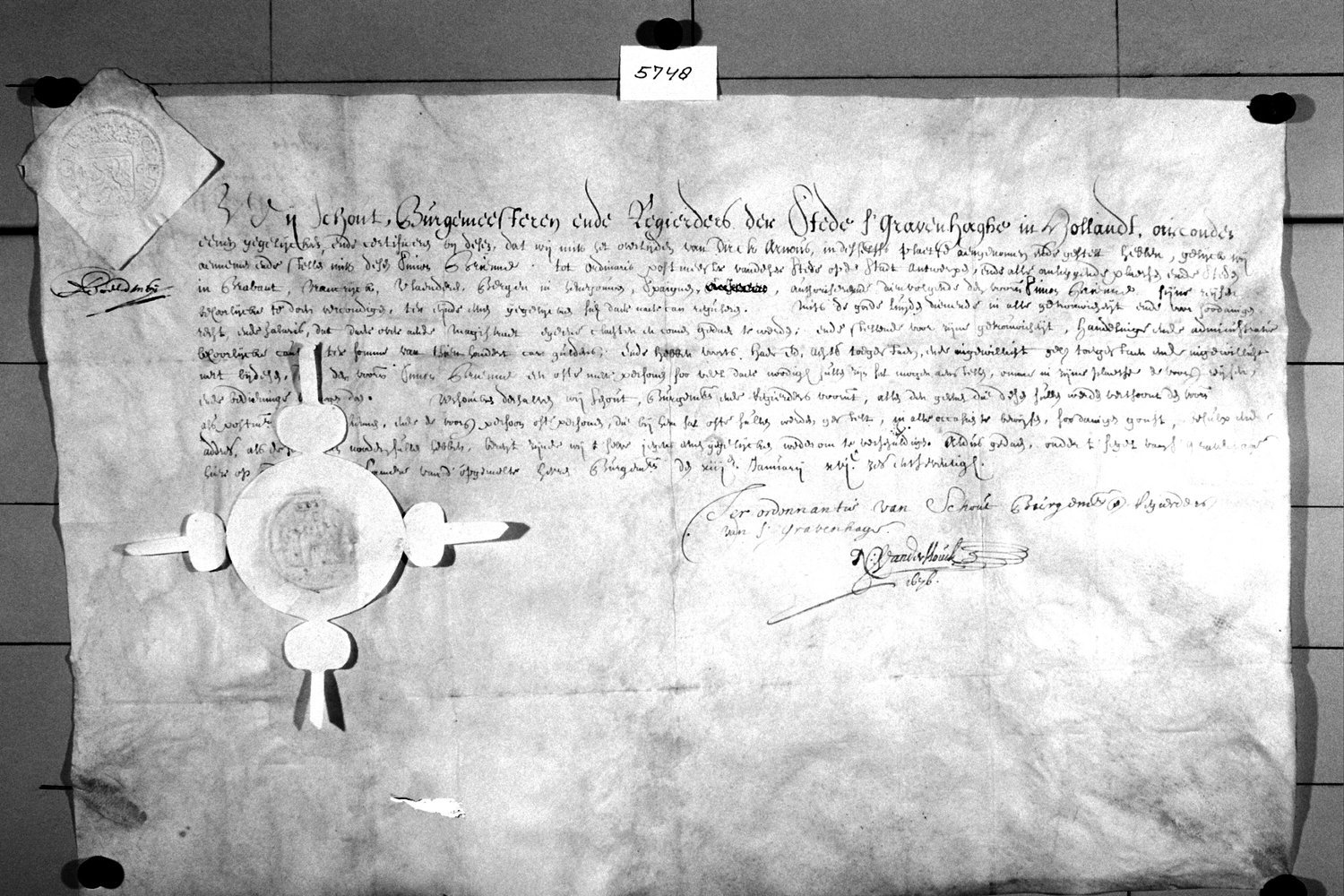

Charter appointing Simon de Brienne as postmaster, 1676, Weeskamer nr. 11851, Municipal archives, Delft.

The appointment

On 13 January 1676, the burgomasters of The Hague appointed Simon de Brienne, née Veillaume, to the lucrative office of postmaster. He would be responsible for all mail to and from “the city of Antwerp and all surrounding places and cities in Brabant, France, Flanders, Mons in Hainaut, and Spain,” as the charter decrees.

Ten years later, Marie Germain was appointed as postmistress alongside her husband.

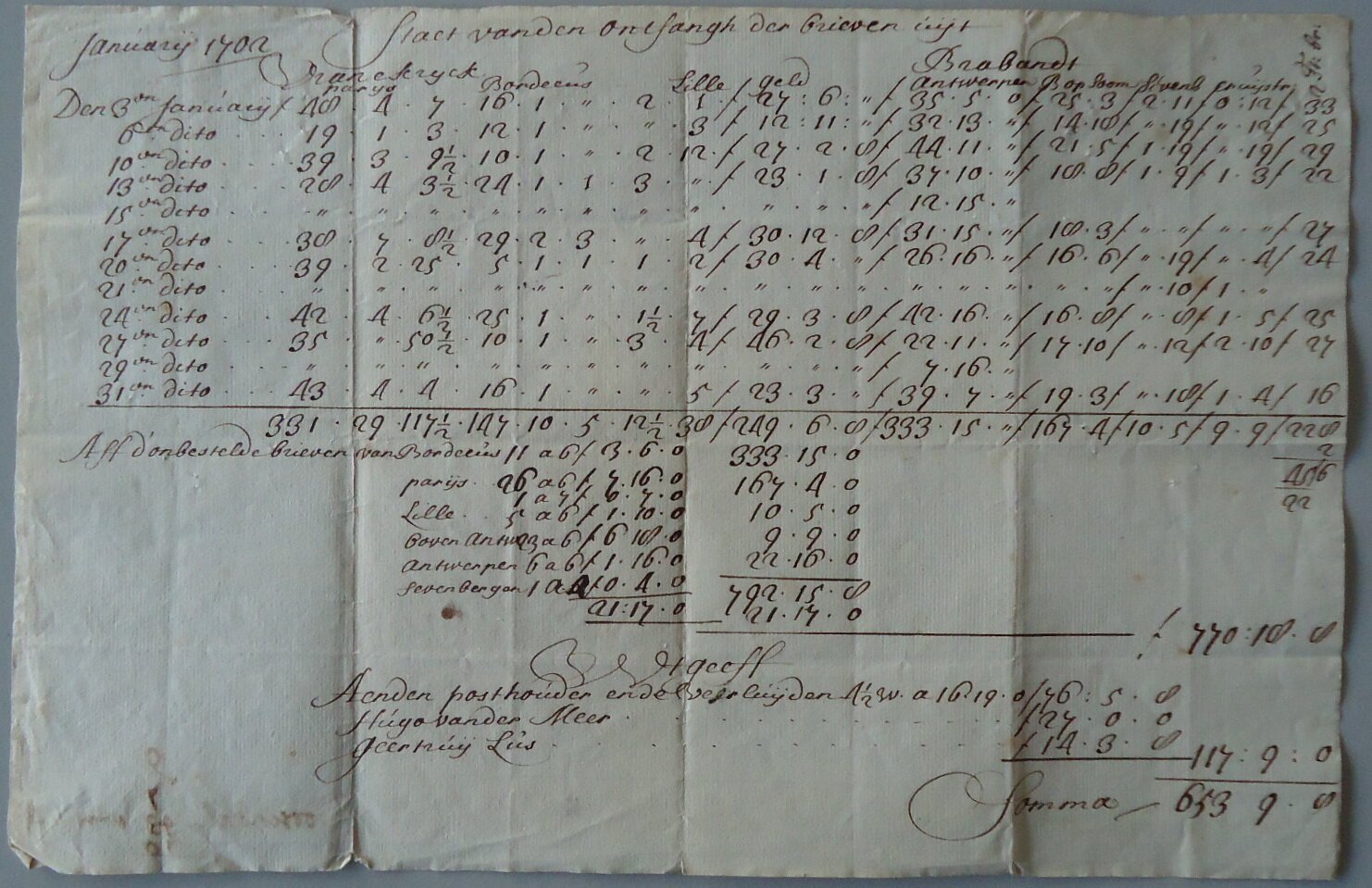

Account of letters received from France and Brabant, January 1702. Sound and Vision, The Hague.

The post office

The day-to-day running of the post office was entrusted to a commissary, Hugo van der Meer. He also kept meticulous accounts, like the one shown here. It records all letters received from France and Brabant in January 1702.

Geertruy Lus, described in the accounts as bestelster (delivery woman), was responsible for actual mail delivery.

By outsourcing the nitty-gritty postal work, Simon and Marie could move to London in 1689, following William of Orange, who had recently become King William III of England during the “Glorious Revolution.” The Briennes served William at Kensington Palace, and only returned to The Hague in 1700.

Silver medal, Roelof Meulenaer. Inv. no. 01156, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

50-year anniversary

In 1688, Simon and Marie’s colleague in Amsterdam, postmaster Roelof Meulenaar, celebrated his 50-year anniversary. He did so by commissioning a silver medal for his children. It shows a postillion blowing his trumpet. The reverse side reads:

Roelof Meulenaer

die vyftich iaren langh. postmeester is geweest.

heeft t’ bitter wel gesmaeckt. doch t’ soetste aldermeest.

Roelof Meulenaer,

who has been postmaster for fifty years,

has tasted the bitter, but the sweetest the most.

Roelof Meulenaer, portrait by Ferdinand Bol, 1650. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Maria Rey, portrait by Ferdinand Bol, 1650. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Postmaster Twent and his sons, painted by Martin de la Court, 1695. Inv. no. 27413, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

All in the family

The postmaster of Delft, Lambert Twent, showed off his prominent position by having himself and his sons portrayed by painter Martin de la Court in 1695.

The painting offers a unique insight into a postmaster’s household. While Twent – sporting a wig and an expensive silk gown – keeps the records, his sons Nicolaas, Zeger, and Abraham help him seal, bind, and order the letters. Adriaen plays with the dog on the right, while on the left a postillion blowing his horn is about to deliver a new pack of letters.

Keeper of the Wardrobe

Simon de Brienne also amassed a fortune as chamberlain and confidant to Stadholder Willem van Nassau, Prince of Orange – from 1689 King William III of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The Briennes came to England with William’s Glorious Revolution of 1688.

A trusted servant in the royal household, Simon was appointed Keeper of the Wardrobe at Kensington Palace in 1689, an office he and Maria sold a decade later for £1550 plus a cask of the best Burgundy wine. Soon thereafter they moved back to The Hague, still supervising the postal routes.

“the piggy bank”

Maria Germain and Simon de Brienne died in 1703 and 1707 respectively. Not having any children, they bequeathed their belongings to the orphanage in Delft. Among them was a trunk.

The Briennes’ trunk is a unique artefact. It is plastered with several wax seals and waterproofed with seal skin.

The contents of the trunk are truly extraordinary – around 2600 letters in French, Spanish, Latin, Italian, Dutch and English – from various writers, with a multitude of different kinds of paper, enclosures, seals postal marks, and folds.

The letters from the Brienne trunk offer an extremely rare window into the early modern world of letters and postal systems.

Continue to Room 2 to check it out!

Page added: 12 November 2023