Exhibition Room 5

The Material Letter

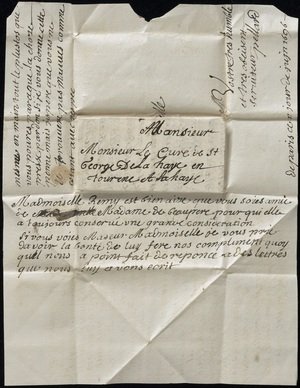

The obvious tools for writing a letter are pen and paper. But so much more was involved in signing and sealing a letter in the seventeenth century.

The Material Letter

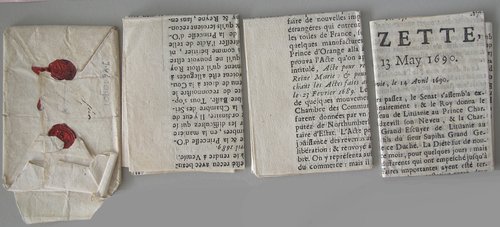

Letters aren’t just the stories they contain written within. When we take a closer look at the letters as objects, we can also recognise that their material properties tell a story too: the paper and ink that were used, the wax seal applied, and the miscellaneous materials hidden inside.

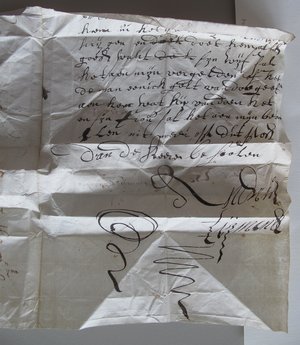

DB-0365.

Paper

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most letter-writers in Europe used paper. In medieval times, letters were often written on parchment, which was made of the skin of sheep and goats. But although very durable, it was also very expensive.

From the sixteenth century onwards, paper became the most important material for most everyday written communications. Paper mills manufactured paper from the pulp of wood, old clothes, and other fibrous substances. Though still not cheap, paper became available in larger quantities. Combined with a rise in literacy, the spread of this technology underpinned an explosion in letter-writing across Europe.

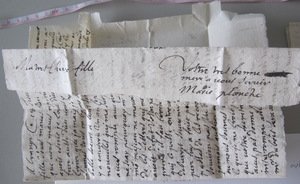

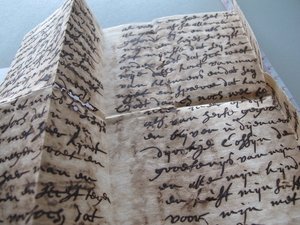

A letter-writer in the early modern period would have to prepare their paper by hand, cutting it to size and trimming it, preparing the surface to absorb ink, folding in a margin to help with neat writing, then folding it up and sealing it for delivery.

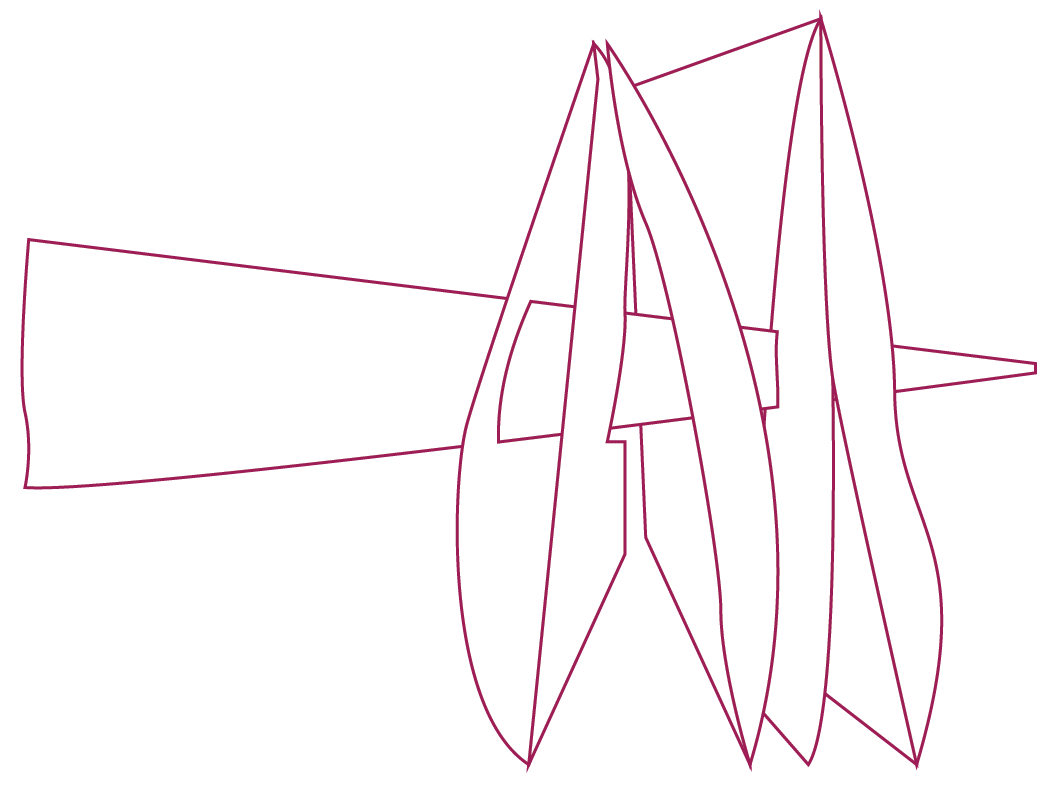

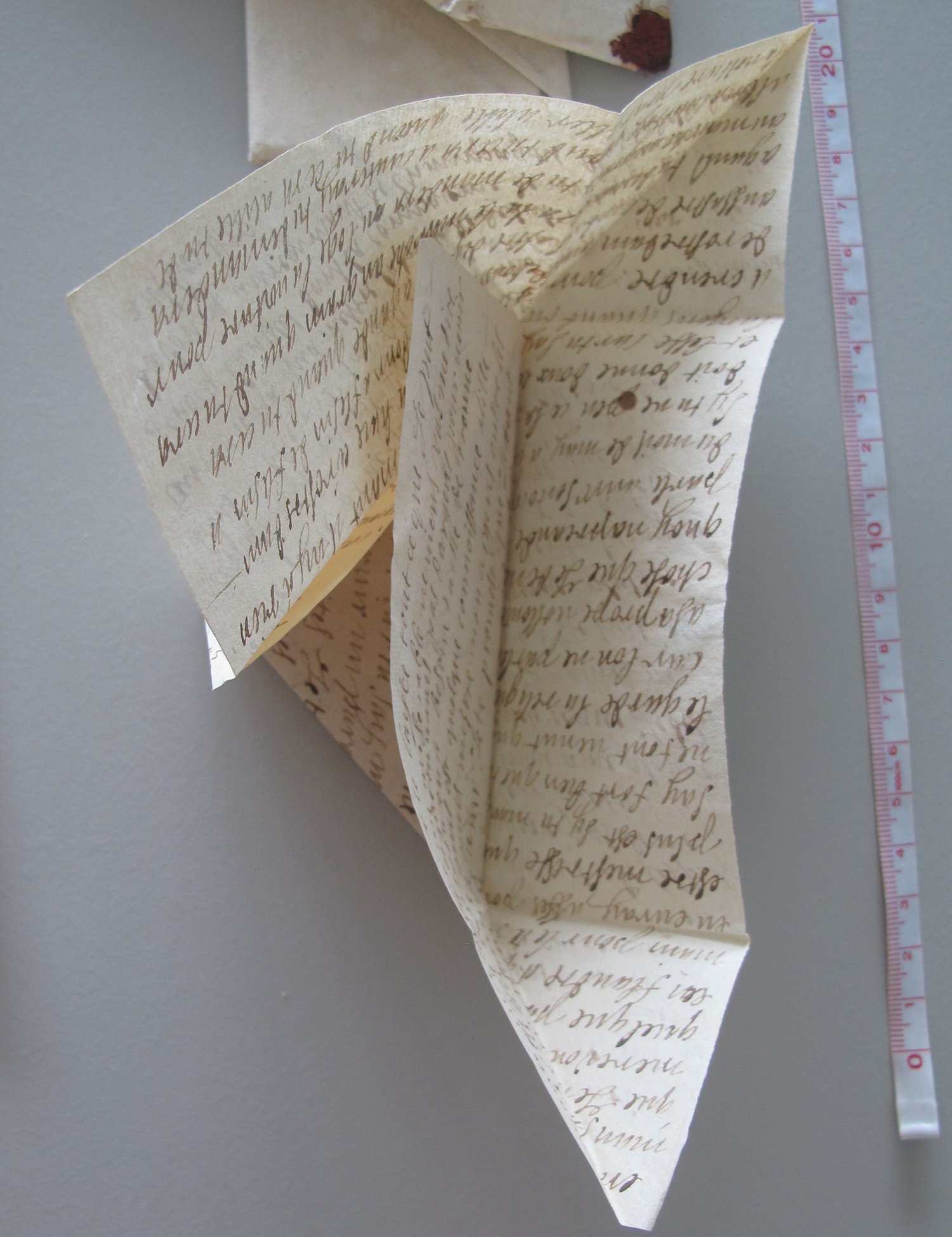

DB-2040 Pleated letter.

DB-2146. Check out the detail of the seal in the "seals" section.

DB-2004

DB-752.

DB-752. Handling letters folded for 400 years requires care otherwise the paper may tear at the places where the folds intersect each other.

DB-1876

Detail of an opened love letter. The brown stains are from the adhesive, which has darkened over time, once used to secure the letter shut after it was folded into an intricate diamond-shaped enclosure.

DB-1977

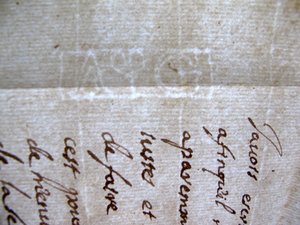

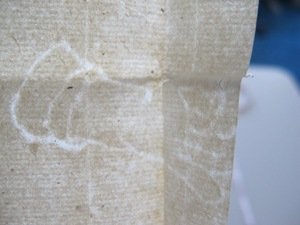

Watermarks

Watermarks are a faint design found in paper sheets, usually only visible when the paper is held up against the light. They are a product of the manufacturing process, where wet paper fibres make contact with wire designs in the paper mould beneath them. Watermarks could often be elaborate and personalized, as in the images here, and can help identify the paper mill where the paper was produced.

DB-1986

DB-2240

DB-1118

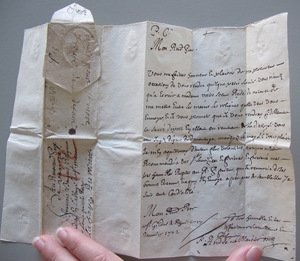

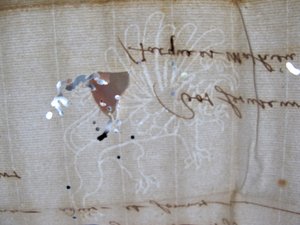

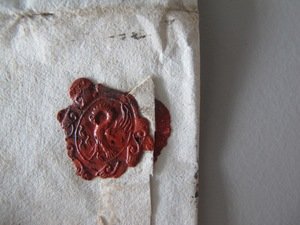

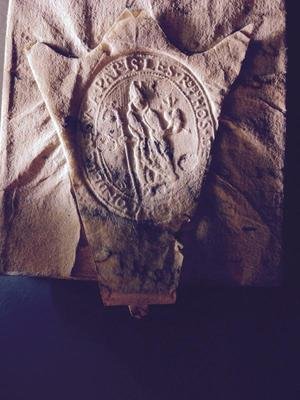

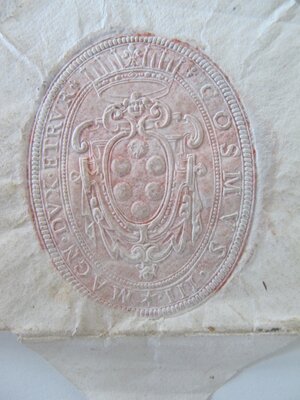

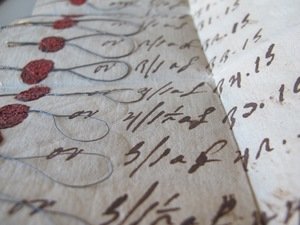

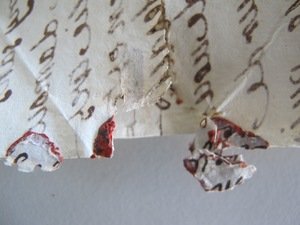

Seals

The seal is often the most visible sign of a letter’s security mechanism. A seal usually consists of wax or starch wafer used to join two panels of paper together. A unique design carved into the face of a seal-stamp – for example a coat of arms – could be pressed into the melted wax to give the letter a guarantee of authenticity.

DB-2240

DB-1653.

DB-2124.

These signet also act as an adhesive to hold down metallic thread samples.

DB-2124.

DB-2124. This wax seal secured shut the wrapper that enclosed the sheet of metallic thread samples.

DB-1953.

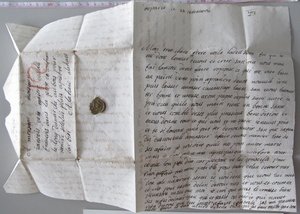

The signet is impressed through a bright red starch wafer which was sandwiched between the folded, slit, and tucked sections of this letter packet to create this covered authenticated seal while enclosing the letter.

DB-1910.

DB-1465.

DB-0102.

DB-1722

DB-0680

DB-0858

DB-0234

DB-0713.

DB-1100

DB-1162.

DB-2146.

DB-2159.

DB-0787.

DB-0279.

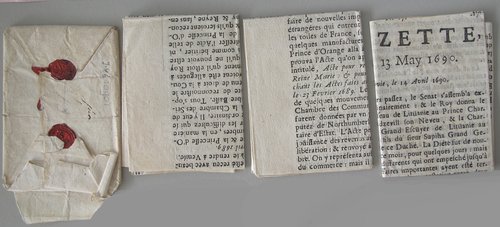

Inserted objects DB-1820. Many of the letters in the Brienne Collection have one or more letters enclosed within. The letter enclosed in this example remains sealed shut.

Inserted materials

Just as today we attach documents to our emails, early modern letter-writers sent along all kinds of materials in their messages. In these images family members shared pieces of newspaper and cloth merchants included pieces of fabric and textile by way of prospectus. One fiancé even sent along a beautiful hand-coloured drawing of a bird. Sadly, none of these letters ever reached their intended recipient!

Inserted objects DB-2124.

DB-1320. Detail, inserted textile swatches.

DB-1320. Letter with inserted textile swatches.

DB-2240.

This little token is referred to as a "poesieplaatje" in Dutch.

DB-2240

Inserted objects DB-0901.

DB-0178.

DB-0998.

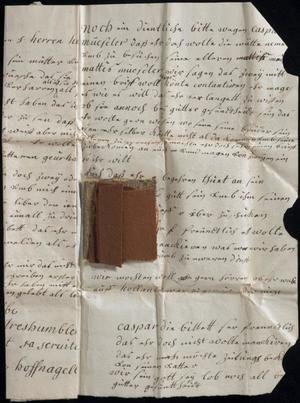

Burns and ink corrosion

Letters show evidence of both wear and tear and intentional manipulations. For example, cuts were made in the paper to produce paper locks, and slits were made in the paper to thread those locks through. Adhesive was often then applied over these locks – but burning wax could set fire to parts of the paper, if the letterlocker was not careful about how it dripped.

Ink too, can cause damage to the paper. Over time ink (which was made using acidic elements) can corrode through paper. What’s more, the handling of the letters throughout the years also leaves its marks, as paper is torn by its original recipient, or unfolded and refolded over the years by researchers.

The materiality of all the letters in the Brienne trunk tells a story about these letters as objects. Museum and library curators and conservators today face serious challenges in deciding how to preserve this kind of evidence for researchers. For example, the unopened letters in the Brienne trunk are going to remain unopened so that they can be studied in their closed state. This is not common practice in archives – but once letters like these are opened, their evidence changes forever.

Hindric Sebastian Sommar, Letter rack, Trompe l'oeil, c.1750. Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

Letter Materials

We’ve seen the material properties that letters from this period commonly exhibit. But what materials and objects did people use to write and send their letter in the first place?

Wunsch Teaching Collections, TC0003, MIT Libraries

Quills and nibs

Quills were common writing implements made from bird feathers, which were cut and shaped by hand. In fact, the word “pen” derives from the Latin word penna, meaning feather. Numerous quills were used in this time, including feathers from geese, pheasants, and swans – which is your favourite? And would you rather cut and shape your own feather quill, or buy a fashionable new metal-steel nib?

“Raadsheertje”, 37444, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

Ink and ink pot

Ink was often a home-made product at this time, sometimes using “oak galls,” or perhaps soot. The main substance would have to be broken down using an acidic substance – if you were in a real pinch, you could even use urine! Once you made your ink, you’d keep it carefully in a pot so it wouldn’t dry up. After using it to write your letter, you would sprinkle “pounce” (a kind of fine sand) over it, or blotting paper with a blotter.

Wunsch Teaching Collection, TC0003, MIT Libraries

Wunsch Teaching Collection, TC0003, MIT Libraries.

Awls

An awl is a sharp pointed tool, which could be used to stab holes through a letter. We often see little holes in letters, which could be used to thread silk floss through in order to tie the packet shut. If you were receiving a lot of mail and wanted to store it somewhere near to hand, you might stab holes through your letters and hang them up on a string in your office. A nice sharp awl would come in very useful.

Wunsch Teaching Collections, TC0003, MIT Libraries

Sealing Wax

A bright blob of sealing wax can be one of the most attractive features of an early modern letterpacket. In this period, sealing wax was made with a combination of beeswax, shellac, rosin, and turpentine, and turned into sticks which could be melted over a flame. The wax would then be dripped strategically onto the letter so that two sections could be stuck together, preventing access.

Many wax seals that we find on letters today are red, but we’ve also found green and black sticks (black could be used to signify that the letter brought news of or condolences for a death). The Brienne Collection even contains wax flecked with real gold – a sign of wealth and good taste.

Wunsch Teaching Collections, TC0003, MIT Libraries

Wafers

Not the light, crisp biscuit, but a small disc of dried paste used for fastening letters or holding papers together. In order to make your wafer sticky, you would moisten it on the top and bottom before pressing the letter down on both sides. Alongside sealing wax, wafers are one of the most common adhesives in the early modern period, and gained in popularity through the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Seal-stamps and Signets

Once your adhesive was carefully placed where you wanted it on the letter, you could use a seal-stamp or signet ring to press down into it, firming up the adhesion while also imprinting your own personal design into the hardening wax. A seal-stamp has a design carved into its face back-to-front, so that it comes out the right way when stamped. These designs can be very personal, like family crests. Some letter-senders might use a signet ring instead, performing much the same function but carrying their stamp around on their finger. What would you have on your personalized design?

Wunsch Teaching Collections, TC0003, MIT Libraries

Wax jack

This fancy device holds a coiled, flammable taper so that its end is ready to be lit. That flame was then used to melt sealing wax. A regular letter-writer might like to have a wax jack on the desk, ready to go.

Detail of Postmaster Twent and sons, by Martin de la Court, 1695. Sound and Vision, The Hague.

How many letter materials do you recognise in the Twent painting?

Page added: 12 November 2023