Exhibition Room 3

A musical letter

DB-0011, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

A musical letter

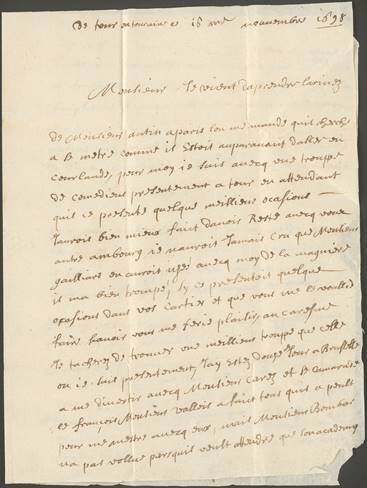

From Jean-Baptiste de Crous to fellow musician, 1698

Remembering shared experiences was (and is) an important part of keeping in touch, particularly for the elite performers who lived and played together across Europe in Brienne’s day.

Writing from Tours, bassist Jean-Baptiste de Crous contacts an old acquaintance in The Hague. The two used to play together in the orchestra of the Duke of Courland. When the duke died, they parted ways.

This letter from De Crous demonstrates that keeping in touch was not just about finding the next gig, but about true camaraderie maintained across long distances. The musicians that De Crous addresses in this letter as “my old friend” or “my dear comrade bassist” worked with him in France, Germany, and even faraway Latvia.

De Crous, who signs off as “your servant and comrade,” would reunite with some of them at the Swedish court a year after this letter was sent.

Pieter Rombouts, Bas viola da gamba, 1708. Gemeentemuseum, The Hague.

Please click here and ‘play’ – enjoy the music while reading

This is a nice melancholy piece featuring the violas da gamba.

De Crous joined the royal band of Sweden in 1699. The ballet was written to celebrate the Swedish victory at Narva in 1700. So you’re listening to music that De Crous actually played!

This is a viol like what De Crous might have had.

It is a musical instrument, made of red-brown varnished pine and maple wood.

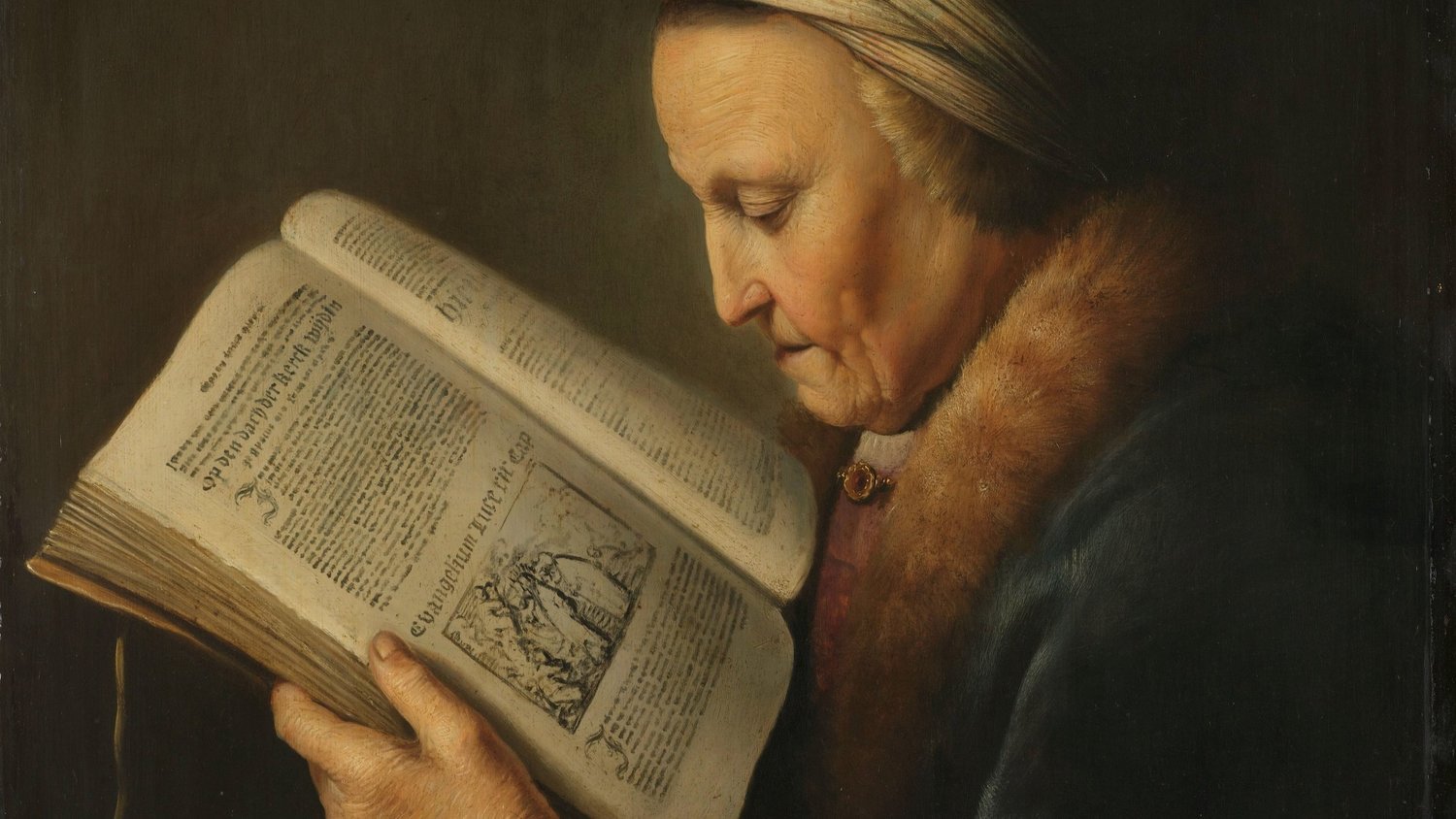

Gerard Dou, Reading Woman, c. 1631. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

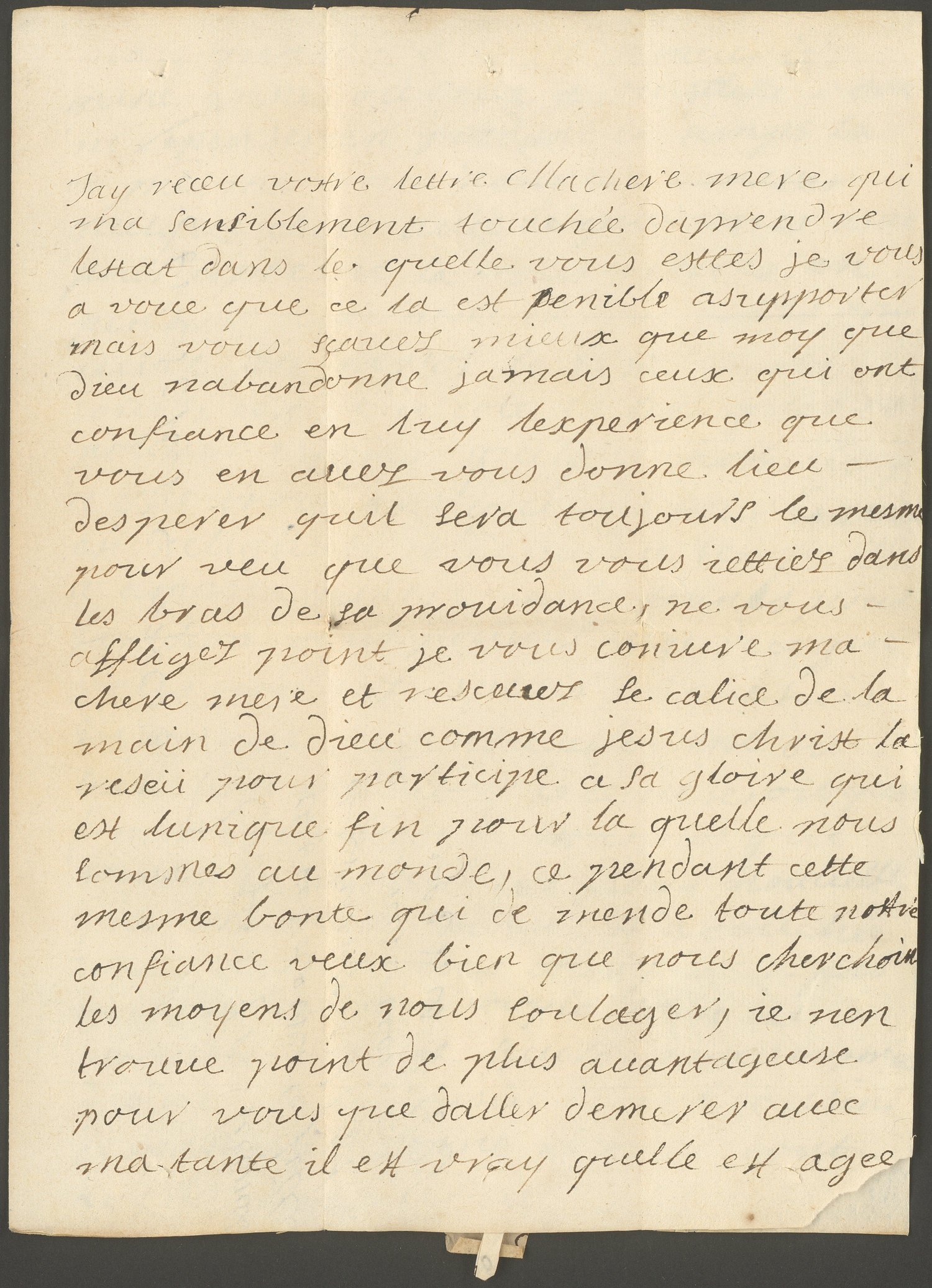

A consolatory letter

Daughter to mother, 1691

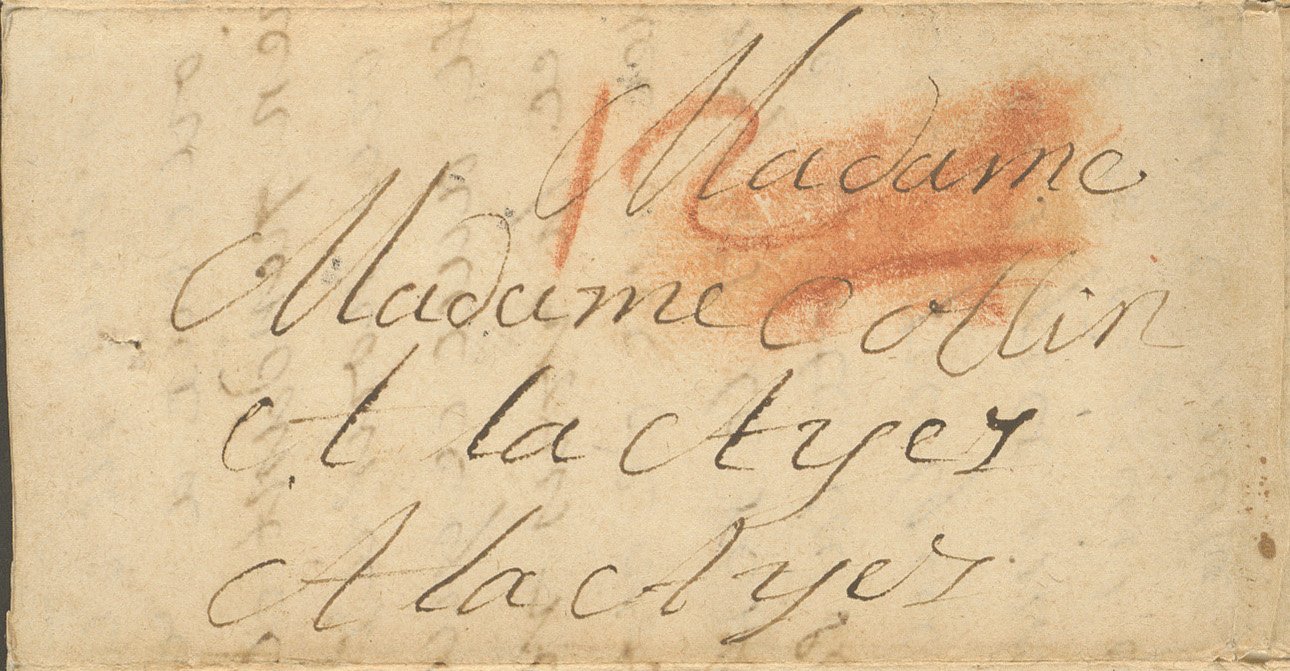

In the seventeenth century, women wrote at least as often as men. In the summer of 1691, a nun wrote this letter to her sick mother, madame Collin. Apparently the mother had already complained about her unfortunate condition and her daughter comforted her with religious advice:

DB-1465.

“You know better than I do that God never abandons those who have faith in him. Your own experience gives hope that he will always be the same, provided that you throw yourself in his providential arms. Don’t torment yourself, I beg you, my dear mother, and receive the chalice from God’s hand just as Jesus Christ received it to participate in his glory.”

This letter ended up in The Hague by accident. Hugo van der Meer, Brienne’s deputy, also noted the mistake, as he wrote down “France” on the back of the letter. The French postmasters probably mistook the address “La Ayes” for “La Haye” (French for The Hague).

View

DB-1465, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

DB-1465, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

Gerard ter Borch, The Letter, c. 1650. Hermitage, St Petersburg.

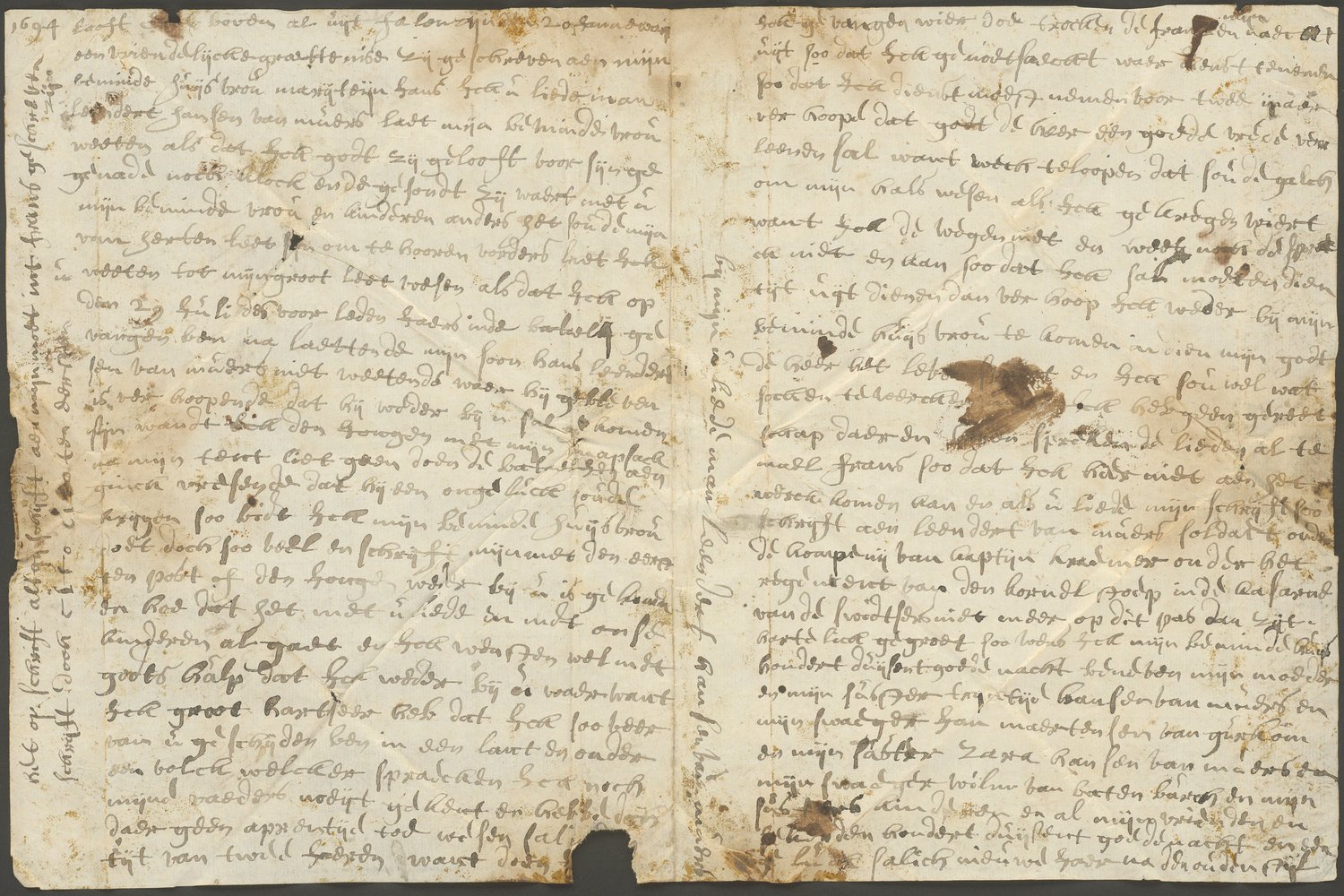

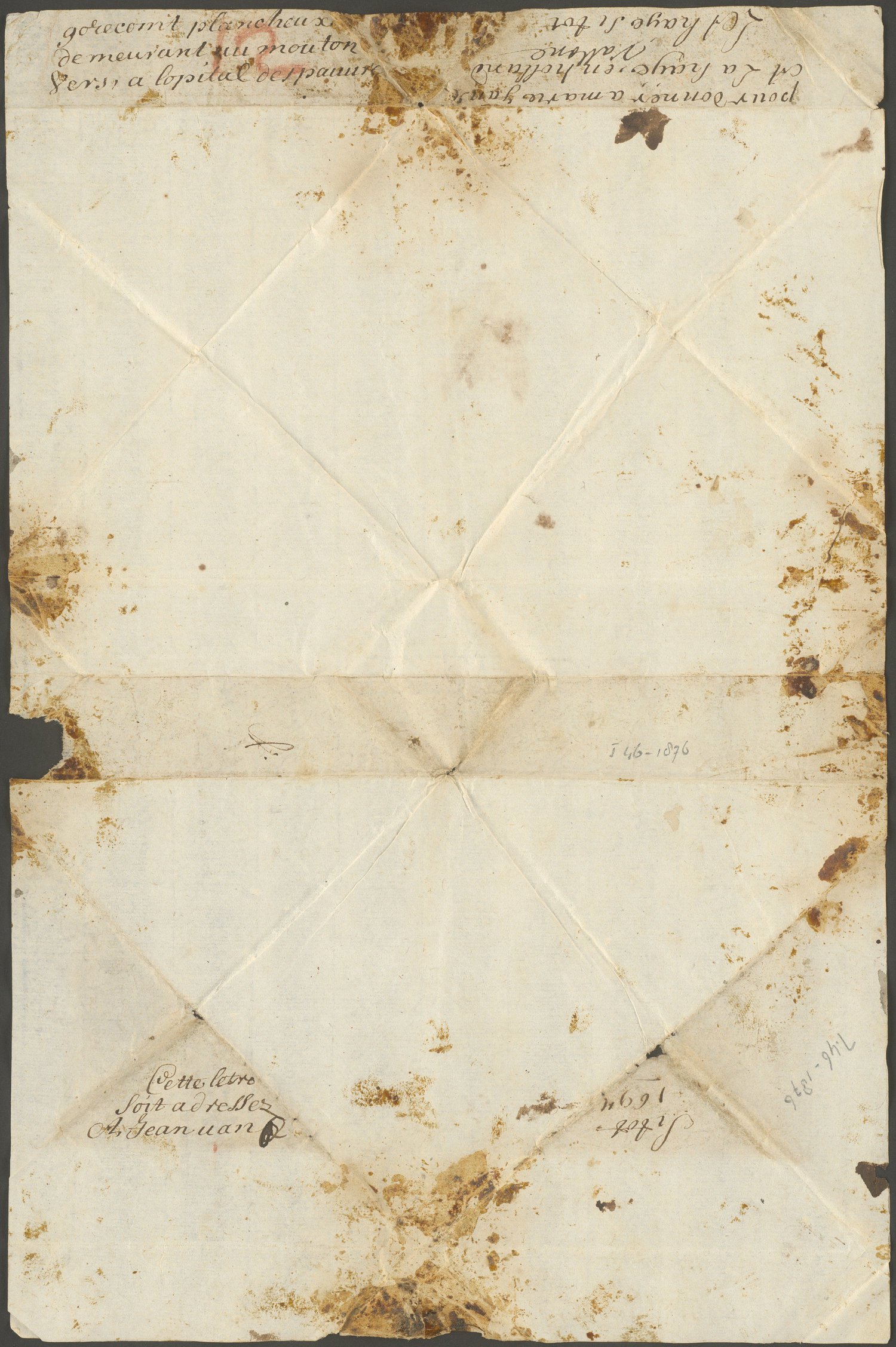

A heartbreaking letter

Leendert van Muers to Marie van Muers, 1694

In 1694 Leendert Jansen van Muers, a Dutch soldier, wrote a letter home to his wife in The Hague. He tells a sorrowful tale: he has been taken prisoner by the French on 29 July 1693, during the Battle of Neerwinden, one of the most famous encounters between the French army and Dutch-English forces during the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697). Leendert’s son Hans was fighting alongside him, but he doesn’t know what has happened to him – hopefully he’s made it safely back home to The Hague; Leendert is begging his wife to send him news.

He’s also having a hard time in captivity, beautifully capturing the sense of loss and displacement as he writes to his wife that:

DB-1876, Sound and Vision, The Hague

“I wished with God’s help that I were with you again, because my heart is aching to be separated from you, in a country and under a people whose language I nor my fathers ever knew.”

He was eventually forced to enlist in the French army for two years, and is hoping it will soon be peace again, allowing him to return home. He closes the letter by wishing his wife, kids and family “a hundred thousand good nights, and a happy new year.”

But alas, the letter never arrived.

DB-1876, Sound and Vision, The Hague

Gerard ter Borch, The Messenger, c. 1650. Mauritshuis, The Hague.

A business letter

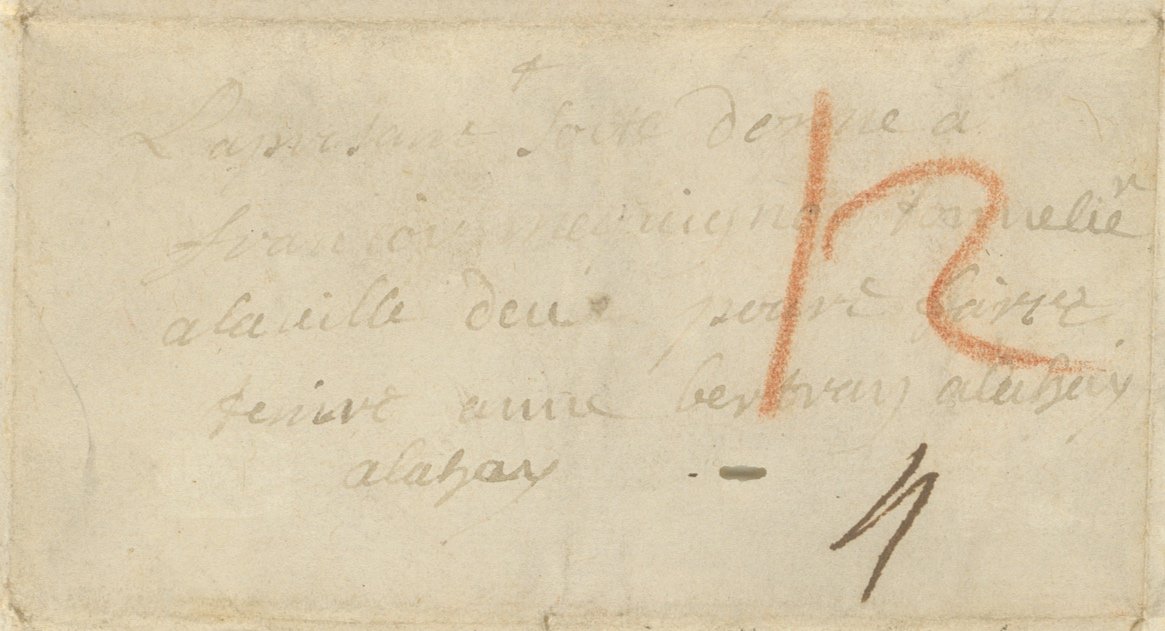

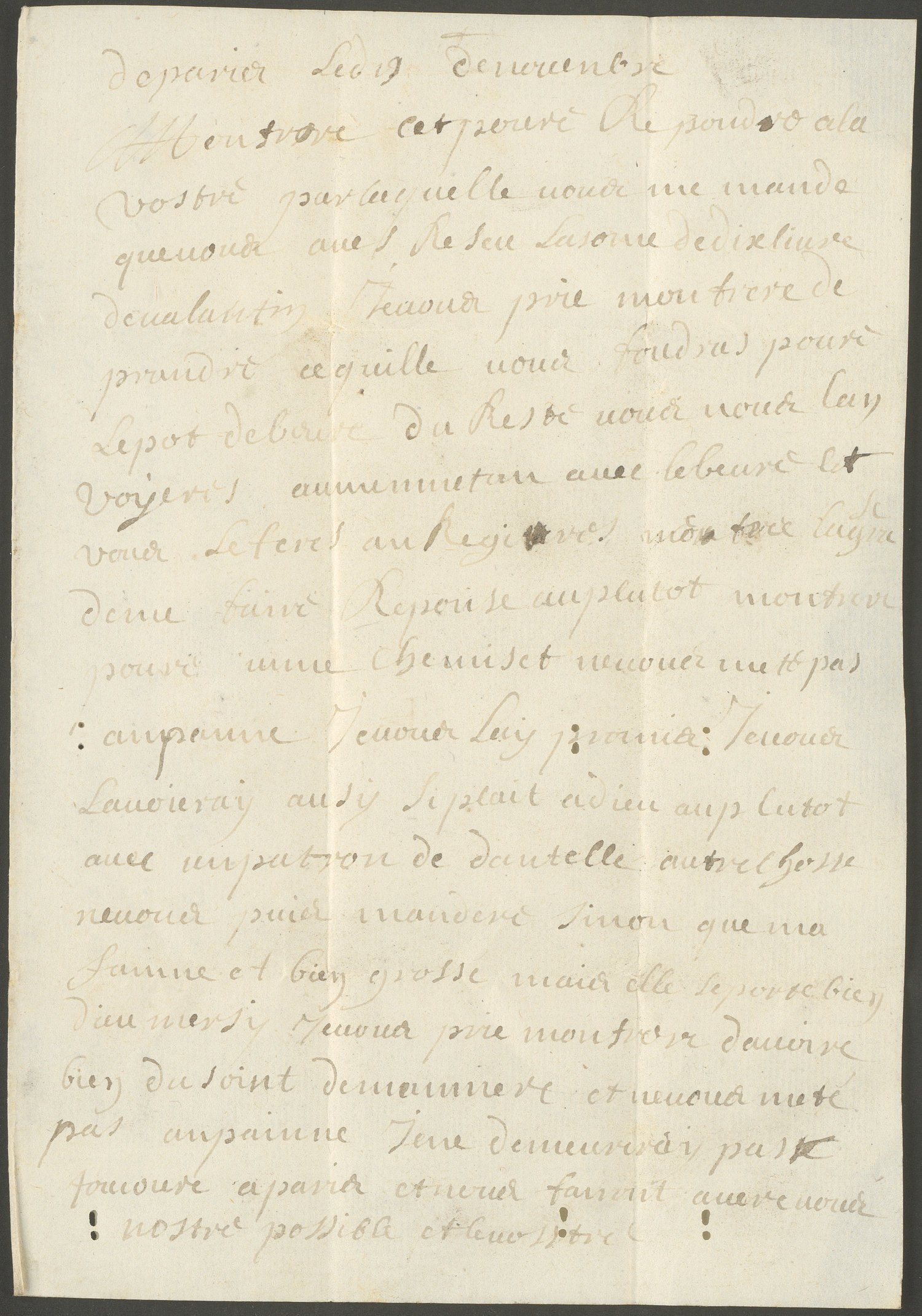

Gabriel Bertras to his brother.

This is an example of how families kept in touch, and also kept up their family businesses.

Gabrielle Bertras writes a short letter from Paris to his brother in The Hague. The author thanks him for sending money. Both appear to be active in the textile trade, because he promises to send a shirt as well as a pattern for lace.

Beyond business, the letter includes the news that Gabrielle’s wife is expecting a child, and that everyone is healthy and happy.

That the family was doing well can perhaps best be seen in the materials of this letter: the fine paper bears three seals, flecked with gold leaf. The letter is a bifolium. The first leaf folds into a different pattern than the back leaf which forms the outer address and sealing panels.

DB-2159: “Francois Mequigno tonnelier; Me. Bertras”

DB-2159, Sound and Vision, The Hague.

Keeping in Touch

Sending letters was not for the happy few. In early modern Europe, everybody wrote and sent messages: men and women, friends and family members, lovers, merchants, diplomats, musicians, and even prisoners of war.

The Brienne chest of undelivered letters is clearly a treasure trove of unique voices from the past.

Page added: 12 November 2023